Tanker Accidents: Double Hull = Double Safety?

The US Oil Pollution Act and its double hull- requirement was brought about by the oil spill from the "Exxon Valdez" accident, but experts disagree over whether double hulls will effectively hinder such oil spills in the future.

When the "Exxon Valdez" ran aground in the Prince William Sound, Alaska, on 24 March 1989, it started the political process that led to the US Congress passing the Oil Pollution Act, OPA 90. This is probably the most important national legislative action ever to affect shipping, and it has great international repercussions, as the US crude oil imports represent the single most important tanker market in the world.

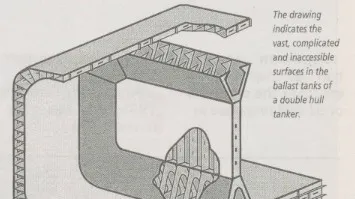

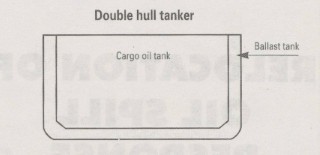

One of the main elements of the OPA is the first-ever legal requirement that tankers be fitted with double hulls in order to reduce the risk of oil spills after an accident.

This may sound just fine - double hull means twice as safe, right? - but whether double hulls will really reduce the risk of a Valdez-type oil spill has turned into one of the most hotly debated issues in the maritime community in a good few years.

Tormod Rafgard, managing director of Intertanko, the International Association of Independent Tankers Owners, voices his double hull-doubts in a rather diplomatic way: "The double hull configuration has several operational advantaged, and it will prevent many small oil spills, for example in slow-speed groundings and collisions, but double hulls are less likely to prevent major disasters."

In the case of the "Exxon Valdez", for one, a double hull would probably not have made much of a difference. According to MIT professor Henry Marcus, who chaired a US National Academy of Sciences committee commissioned to study tanker design and operation for the OPA, "double hulls would not have completely protected the Exxon Valdez from spilling. The impact was too great. Both hulls would have been punctured."

Other, independent studies suggest that a double hull VLCC (Very Large Crude Carrier, more than 200,000 tons) would be holed at speeds as low as seven knots. Most modern tankers go about their business at 13 - 14 knots.

TheMarcus-committee's general conclusion, however, was that double hulls appear to offer the best method of limiting oil pollution after an accident, so that is now the law.

One serious argument against the OPA is that it is an unilateral action, and thus departs from the internationally accepted principle that such rules be drawn up by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the maritime body of the UN. The IMO already had a comprehensive set of rules to prevent pollution from ships, the so-called Marpol- convention. Equivalent alternative?

In its latest amendment to Marpol, the IMO supports the principle of double hulls becoming the international norm, but it does not exclude alternative designs, "acceptable equivalents".

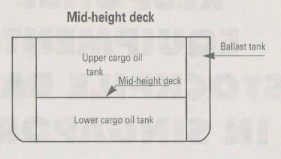

One such alternative is the so-called mid- deck design; single skin vessels with a horizontal division of the tanks. If the bottom tank is holed, i.e. in a grounding, hydrostatic pressure would prevent oil from being spilled. Deployment of all ballast spaces within the tanker's sides would also increase the collision protection of the cargo tanks from 3-4 metres in a double hull structure, up to 6 metres in a mid-deck vessel. This design was supported in IMO in 1991-1992 by Intertanko and others, who believe it offers the best protection in high energy groundings. Even the US-study found the mid-deck "possibly superior" to double hulls in high energy groundings, but then dismissed it as it is yet unproven.

This is more or less what Intertanko's technical experts hold against the double hull VLCCs designed to meet the latest legislation. These "do not have the benefit of operational histories provided by observation over an extended period", according to the experts. There could be new, unknown technical problems.

"It is highly important," Tormod Rafgard says, "that we do not adopt regulations that shut the door on future design developments leading to even safer and more environment- friendly ships." Who Will Pay?

In the end of the day, the consumers would eventually have to carry the extra costs of safer ships. Theoretically, that is.

So far tanker owners (and their patient financiers) have been left to foot the bill, as the tanker rates are determined almost solely by supply and demand of transportation capacity, rather than by the quality of the tonnage.

According to Intertanko's Rafgard, double hulls add approximately 10-15% to a VLCCs construction cost which is presently between USD80 and 90 million. Due to substantial capital costs, these new tankers thus need rates of nearly USD 50,000 per day to break even, and justify newbuildings.

So far this year VLCC rates have averaged only USD13-14,000, which is only half of what even a 20-year old vessel needs to break even.

The average age of the world's large tankers is currently around 14 years - the highest for almost 50 years - and a substantial fleet renewal is more or less inevitable.

The price consumers and industry eventually will have -to pay for a fleet renewal does seems fairly modest, as the freight element in the price of petroleum rather significant. Even a dramatic increase in tanker rates, for example to USD 50,000 per day, would represent less than 1 % on the price of a litre of gasoline, by the time it reaches the consumer. Another 20 years.

The OPA requires that new tankers, that is those ordered after June 1990 or delivered after January 1994, must have double hulls. Older single skin tankers may continue trading in US waters, but they will be gradually phased out as the OPA's sliding scale rule catches up with them, and they are completely banned from US waters by 2010.

Tankers which discharge at the deepwater Louisiana Offshore Oil Port, or in lightering operations (transfer of cargo to smaller tankers) at least 60 miles offshore, (which is what most of the largest tankers do anyway) will be able to continue until 2015. Thus Exxon Valdez-type tankers will be sailing in US waters for another 20 years, OPA or no OPA.

One undisputed effect of the Act, regardless of age and design of tankers, is that owners and operators of tankers will certainly exercise some extra caution in US waters. The Act introduced a principle of unlimited liability, which means that any shipowner would be effectively wiped out if causing a major oil spill.

The clean-up and damages after the "Exxon Valdez" for instance, is estimated to have cost Exxon between USD 3-4 billion. This is many times more than the value of any of the world's largest shipowners.